Founded in 1989, Yorkshire-based Revolution Software hit the ground running with Lure of the Temptress, an advanced 3D point-and-click adventure that utilised Revolution’s own Virtual Theatre engine. “We were reaching the end [on Lure of the Temptress], and it was the most intense time, testing and checking it,” remembers Charles Cecil, co-founder of Revolution alongside Tony Warriner, Noirin Carmody and David Sykes. “And the problem was, as a one-team, one-project company, we were having to start the next one at the same time.” Hence the development detox for Warriner and Cummins, despatched to a remote Cecil family cottage in North Wales. When the pair returned, they had a 12-page design for Revolution’s next game.

“I said, ‘Look, just go off to Wales for a week and come back with a complete design’,” grins Cecil, acknowledging the enormity of this simple sentence.

So, how did the creative process work? “I don’t know,” laughs Warriner. “It was one of those creative zones, where things sort of flow, where you don’t really know how you’ve done it or how you got into that mode.”

Before Warriner and Cummins set off for Wales, several ideas for Revolution’s next game had percolated around the office: a prime influence was Terry Gilliam’s 1985 film Brazil, and that it should be set in Australia. “So we had that design, that concept of Australia and the cities in the desert,” Warriner continues. “But it was like, what is the game going to be?” The eventual game, sketched out in North Wales, would become one of the most revered point-and-click games of all time.

In Beneath a Steel Sky, the player is Robert Foster, an orphan raised by a tribe of Aboriginals in an area known as ‘The Gap’, a wilderness between towering megacities. When security officers arrive from Union City and cause havoc, Foster is taken back to the city. After giving his guards the slip, he stands on a steel walkway, ready to explore the dystopian city and uncover the innate corruption and exploitation at the heart of this seemingly advanced society.

With Charles Cecil directing, Beneath a Steel Sky – known as Underworld at this point – went ahead into production, using an improved and updated version of Lure’s Virtual Theatre engine. However, in terms of player interactivity and UI, the most significant change was Revolution’s shift away from the traditional point-and-click trend of clicking on listed phrases or commands.

“I think quite early on there was a famous meeting with a producer at Virgin called Simon Jeffrey,” remembers Warriner. “And, to his credit, he said, ‘Get rid of all that shit. Just have the left and right clicks’. And we were like, ‘You’re right!'” Instead of selecting the correct action from a list of verbs and commands, the player simply mouse-clicks to bring up the commands.

“With those listed choices, what you’re doing is wasting the player’s time because only one or two of them will work,” notes Cecil. “By offering just two actions – interact and look – we reduced the number of permutations enormously. But then we attracted criticism about the game being too easy. That’s sort of the price you have to pay.” The interface, refined further for Revolution’s next hit, Broken Sword, is today a template for the point-and-click genre.

For Steel Sky’s story and visual tones, Revolution was keen to move away from the light-hearted approach of the genre’s leader, LucasArts. “I mean, Monkey Island was a great game,” explains Warriner, “but we thought the humour was too much. So we always tried to have a dark, gritty and believable central theme, putting our own dry humour on top of that.” Cecil nods in agreement. “We wanted to have much more credible puzzles that people could work out because they were true to the context, character motivation and environment at that time. We wanted it to be different.”

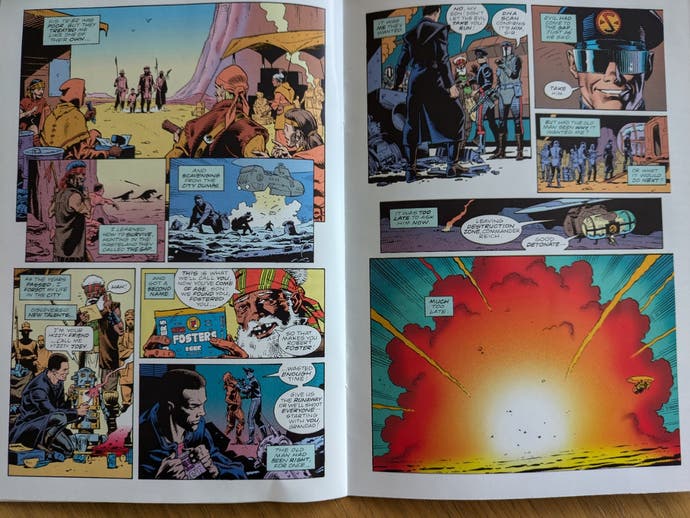

Steel Sky’s stunning visuals were also a world away from LucasArts’ bright and vibrant games, inspired as they were by Brazil and, consequently, the book that inspired the Gilliam movie, which was George Orwell’s 1984. An essential facet here was artist Dave Gibbons, with whom Cecil had worked while at Activision as the publisher attempted to develop a video game version of the alt-superhero graphic novel Watchmen. Cecil takes up the story: “Dave was quite clear that he didn’t actually own the rights [to Watchmen]; I think DC owned them, but I can’t remember why it never moved forward. It was a shame because it could have been a good licence.”

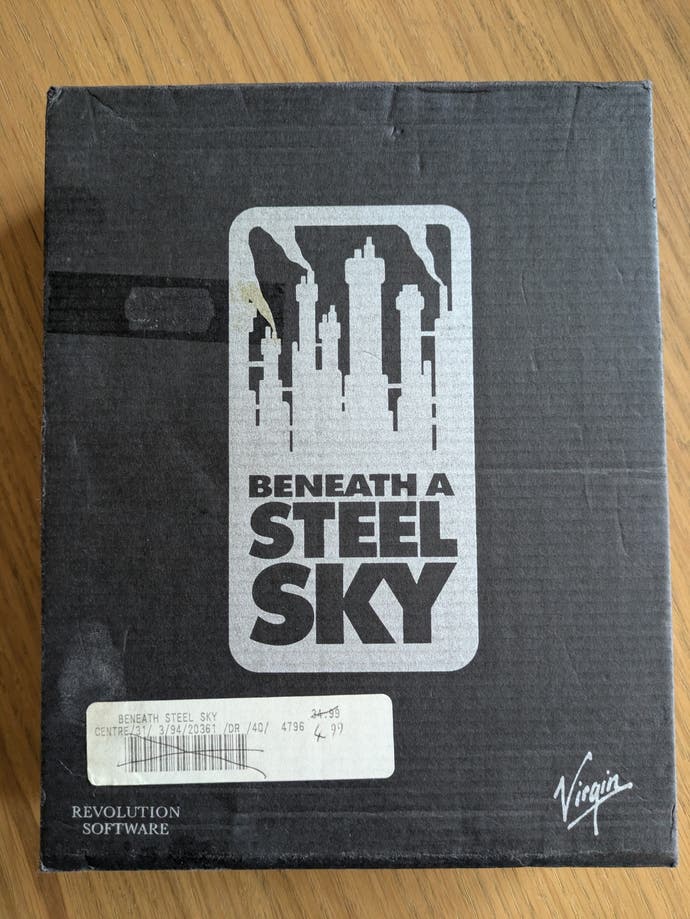

The work was not wasted, however, with Cecil remembering Gibbons when it came to Beneath a Steel Sky. “Dave had a very good name, and it felt like there was an opportunity to not only have him endorse the game, but also contribute. We shipped him an Amiga because he was so excited to start designing characters in DPaint.” Ultimately, Gibbons would also design many of Steel Sky’s emotive backdrops and the game’s overall design. Plus, of course, the comic bundled within the game’s large black box. “I think the Australia setting may have come from Dave,” ponders Cecil, “with the richest and most privileged living high up where the air is cleaner.” Revolution even tried to hoodwink the player away from Australia, using London-esque names such as St James (a real underground station in Sydney). “The whole Australia thing was meant to be played down – but then Dave drew kangaroos in the comic book, which kinda gave it away!” laughs Warriner.

As Beneath a Steel Sky grew, Warriner and Sykes continued development on the Amiga, porting their work across to PC. “By today’s standards, it was not a big piece of programming,” says Warriner. “It would take me two weeks to recreate that engine today, with modern platforms, libraries and so on.” Les Pace and Steve Ince helped bring Gibbons’s pictures to the screen; James Long joined Warriner and Sykes on coding duties; Steve Oades led animation; and Tony Williams and Dave Cummins wrote the script and composed the game’s futuristic music, with the latter also evolving Steel Sky’s futuristic storyline.

“It was quite a small team,” says Warriner, “and everyone was quite talented at their own particular thing, although we were all very different types of people, so bickering was inevitable.” Working from Revolution’s offices in Hull, the team lived and breathed Steel Sky, the developers and their game flooding over into the pubs and bars on weekends. “It was seven days a week, late nights, and a lot of pressure,” Warriner remembers. “And no money. But there was a lot of creative stuff going on.”

In sharp contrast to many video games now (and in the 90s), there were no spreadsheets, focus groups, or publisher intervention. “Steel Sky was just hacked out,” smiles Cecil. “It was just like, let’s make this game and every day, it would inch further to completion. It ended up being so much more than the sum of its parts. It’s a game with soul.” As Cecil further reveals, Revolution’s strong relationship with publisher Virgin helped immensely, and it was severely tested towards the end of Steel Sky’s development. “Virgin were very supportive, and yes, we did keep running out of money. But it found creative ways to fund it a little more.”

One of these methods was to commission an Amiga CD32 version of Beneath a Steel Sky, adding voices to the existing game. At this point, Cecil recounts a tale of recalcitrant Shakespearean actors, overly fond of lunchtime drinking and, err, other recreational activities that adjusted their accents from morning to afternoon. “We kind of struggled through this, and it was absolutely dire,” laughs Cecil. “And in the end, we were saved by Konami. It had licensed the game for the US and said, ‘We’re terribly sorry, we can’t understand a word these people are saying!'” The situation allowed Revolution to jettison what it had already recorded and start again from scratch.

Released early in 1994 on the Commodore Amiga and later on PC, Beneath a Steel Sky was met with universal praise. “As we’d done with Lure, we really innovated and came up with new ideas,” says Cecil. “People seemed to forgive weaknesses if you did that, because things were changing so fast. Back then, we had no direct relationship with our audience; we sold the game to the publisher, who sold it to the retailers, who sold it to the public. We just had to wait with bated breath – fortunately, the reception was fantastic, putting us on an absolute high.”

Steel Sky’s subsequent sales forged Revolution’s relationship with Virgin, inciting a three-game deal with the publisher, paving the way for the incredible success of the Broken Sword series. “[Beneath a Steel Sky] was a pivotal game for Revolution,” muses Cecil. “The scholars of adventure gaming recognise it for its design changes, and for many, it’s a seminal game. And, you know, one of the great privileges of writing adventure games is the people who say that these games changed their lives in the same way as a good film or book. But in many ways, an adventure game can be even more powerful, and it’s a huge compliment when we hear from people who say they were profoundly affected by Beneath a Steel Sky.”

Today, Beneath a Steel Sky is rightly recognised as a defining game in its genre, its legacy detailed further in Tony Warriner’s excellent book, Revolution: The Quest for Game Development Greatness. “Part of the reason I wrote that book was to try and understand how we did it,” he explains, “to try and get a grip on that feeling and maybe reproduce it somehow. Because it was difficult. And it was highly pressured. But creatively, it was terrific.”