Combat is such a routine activity in video games that it often doesn’t feel much like conflict at all. It’s just something done to move the simulation along – a propulsive chore stripped of drama or significance or lasting emotion beyond a vague desire to see what lies beyond whatever it is you’re trying to kill. In Death Of A Wish, combat has substance: it’s a form of redemptive self-expression. The game’s fights are a means of asserting and cherishing yourself in the face of a world that regards you as a deviant, a world whose poison you carry on the inside.

At one point in this brilliant action game, you meet a trainer character who tells you that combat is about more than staying alive – it’s about staying alive with grace and style. “If you fight with beauty and courage, you can push away the darkness,” they tell you. The game’s protagonist, a tortured Cloud Strifey youth named Christian, suffers from a Corruption that creeps up towards 100% every time you perish, and which will cost you some progress if it maxes out.

Death of a Wish | Out Now on PC and Switch

Death of a Wish | Out Now on PC and Switch

Death Of A Wish is a challenging experience, albeit one amenable to the Secret Best Soulslike tactic of running past non-boss enemies (during plot-critical battles, the game boxes you in with diamonds of scarlet energy). If you’re anything like as hamfisted as me, you’ll probably fill up the Corruption bar well before you reach the 5-10 hour plot’s halfway point. Fight with care and discretion, however – avoiding damage, mixing up your abilities, building a combo, and finishing foes quickly – and you’ll deduct a corresponding percentage from your Corruption bar.

The story of Christian’s revenge on the murderous, theocratic Sanctum has elements of autobiography, and the Corruption system specifically feels like a memory of advice given by an older queer person to a younger, struggling one about self-love by means of self-control. Fight beautifully, and you won’t just survive – you’ll be beautiful. You’ll be you.

Death Of A Wish began life as a DLC expansion for 2018’s Lucah: Born Of A Dream. Like that game, it’s a brutal, wonderful experiment that takes some fascinating turns – there’s a section that plays like a party-based RPG, for example. But in broad strokes, it’s a flamboyant, technical hack-and-slash that owes some obvious debts to Bayonetta, not least in its anarchic, anime portrayals of angels and demons.

Like Bayonetta, the game lets you pair weapon or combat styles, called Arias, to create flexible sets of primary and secondary attacks, which you can further develop using modifiers such as Prayer Cards that, say, increase the damage dealt to an enemy’s guard, or extend an Aria’s reach. You also get a hovering Familiar, akin to the drones in Nier: Automata, which performs ranged attacks such as laser beams and flurries of wind. Stir in combos performed by delaying or holding inputs, plus a dodge which becomes a parry when aimed into an attacking opponent, and you’ve got the basis for an engrossing arena brawler. But as with Lucah, what really brings everything together is the visual direction.

Probably the biggest compliment I can pay developer melessthanthree is that I divide my personal understanding of video game visuals into the time before I encountered his work and the time after. I’ve tried to describe it in various ways in different pieces; right now, it reminds me of the scraper-boards I drew pictures with in primary school – silky black squares that hide rainbows, to be gouged into view with a shaky metal nib.

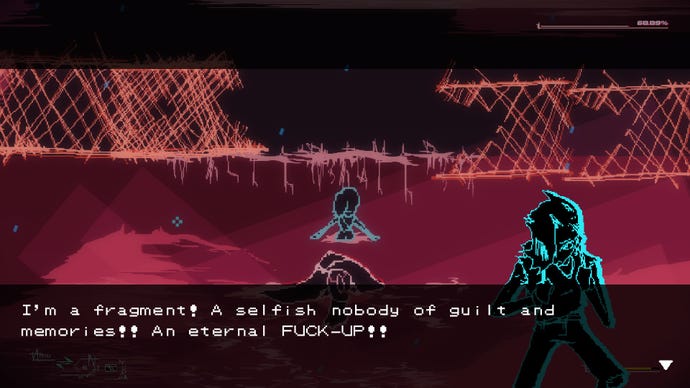

Like Lucah, Death Of A Wish unfolds in a midnight realm where objects, terrain and creatures appear as writhing scratches and squiggles of colour that hover on the edge of incomprehensibility. Straight lines and clean boundaries there are none: everything is fidgety and forever leaking into everything else. There are locations that resemble real places – tent cities and crowded streets, rickety docks and highways – but it’s a powerfully abstract setting where any traces of naturalism float unmoored in a dreamy purgatorial darkness. And then there’s the spectacle of battle, with attacks forming serrated whips of energy that curl across the scenery to a soundscape of whoops and cracks.

It’s absolutely gorgeous. It might also sound desperately ill-suited to a combat game where you often need to parry several enemies in swift succession, while darting away from projectiles, but the other glorious thing about Death Of A Wish is how readable it becomes. The enemies may be shifting clots of fire and gold but they have pronounced, visible and audible wind-ups that allow you to dance your way through the encounter, providing you don’t succumb to the urge to beat them down.

When it gets confusing, it’s often because you’ve overextended yourself by diving into the mob, rather than finding a position where you can focus on a single target. I came away from most defeats with the sense that I’d have prevailed if I’d been a little less hasty. Parrying is both relatively easy, because it’s on the same button as dodging, and vital when fighting the game’s multiple-phase bosses: it’s the fastest way of breaking an opponent’s guard and opening them up for critical hits. In terms of how the combat builds on Lucah, it’s a more aggressive game, with no stamina limitation to check your movements.

Perhaps because it began life as a DLC expansion, Death Of A Wish is also a crisper work of storytelling than Lucah – it’s all about visiting vengeance upon the Sanctum and its handful of bosses, though the plot, of course, thickens as your killing spree extends. Christian’s quest takes you through several regions, each punctuated by fungal outcrops of crucifixes where you can rest and upgrade, with progress typically involving a search for a keycard and some very gentle puzzling.

The writing and narrative presentation are breathless and stark in their handling of heartache and trauma, though lightened a little by the use of different nonverbal speech effects for each character’s dialogue. Often, the game resorts to bald white font on a black screen, screaming its pain outward at the player. It’s not a game you should play if you’re feeling vulnerable – the game’s cutscenes are heavy on lurid religious iconography, and there are expressions of bigotry and bodily injury. But there are moments of drollness and camaraderie, too, and the ugliness is never gratuitous. This is a comprehensively wounded world, with certain elements that need to be excised and others that need to be healed.

As you’d expect from an expansion promoted to full game status, Death Of A Wish didn’t astonish me quite as much as Lucah, but it stands nonetheless as one of the best action games I’ve played – easily up there with the blockbuster Platinum projects it takes inspiration from. For all its bleakness, it’s the kind of experience that reinvigorates your critical faculties, bursting through the fog of diminishing returns and leaving you newly curious about video games in general.