Andrew Morton stood in the sun on the smokestacks of a blast furnace the day the Francis Scott Key Bridge opened on March 23, 1977, watching the first cars cross the bridge. One of many steelworkers at the Bethlehem Steel Corp. at the north end of the bridge, he’d surely forged some of the metal.

Forty-seven years later, Mr. Morton woke up on March 26 to videos he couldn’t believe. The Key Bridge had collapsed after it was hit by a cargo ship.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

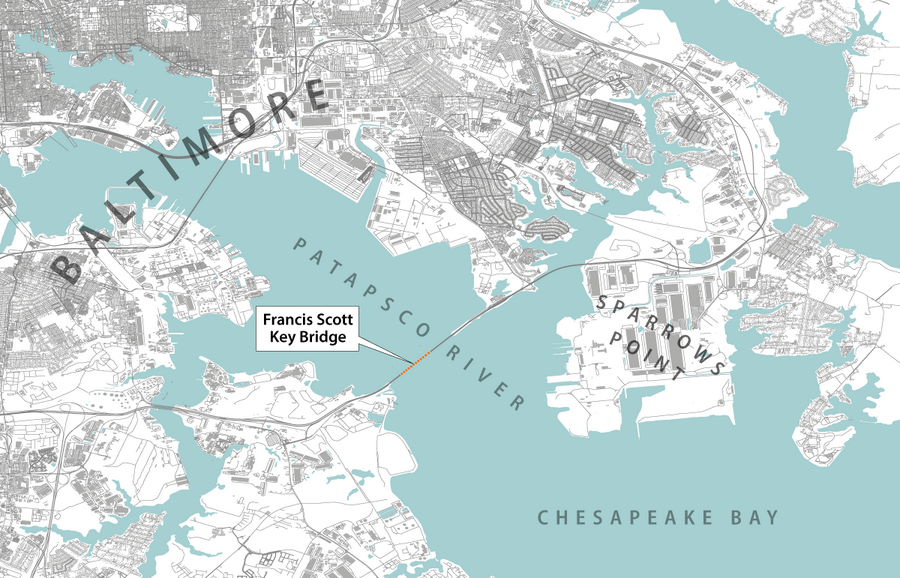

Sparrows Point was a company town that lost its iconic company but persevered. Now, the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge has left residents feeling cut off on the north side of the harbor, wondering what the future may hold for their home.

Not only did Mr. Morton and other residents of Sparrows Point play a role in building the bridge, but also it’s what connected them to the other side of the Baltimore harbor. The town’s roots are inextricably linked with the history of Bethlehem Steel, a manufacturing titan at its height in the 20th century. For over a century it powered the local community, building a company town.

With the wreckage of Key Bridge, Sparrows Point has reentered the spotlight. Today the mill is gone, replaced by warehouses for Amazon, Under Armour, and McCormick. As the economic powerhouses driving the region shifted, so did the community ethos. Still central to that is the legacy of Bethlehem Steel, which helped build World War II ships and iconic landmarks like the Golden Gate Bridge.

Andrew Morton stood in the sun on the smokestacks of a blast furnace the day the Francis Scott Key Bridge opened on March 23, 1977, watching the first cars cross the bridge. For him, the moment had a profound resonance. One of many steelworkers at the Bethlehem Steel Corp. at the north end of the bridge, he’d surely forged some of its metal.

Forty-seven years later, nearly to the day, Mr. Morton woke up on March 26 to videos he couldn’t believe. The Key Bridge had collapsed after it was hit by a cargo ship. “I could not believe that within seconds it was up, and within seconds it was down,” says Mr. Morton.

Not only did Mr. Morton and other residents of Sparrows Point play a role in building the bridge, but also it’s what connected them to the other side of the Baltimore harbor. The town’s roots are inextricably linked with the history of Bethlehem Steel, a manufacturing titan at its height in the 20th century.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Sparrows Point was a company town that lost its iconic company but persevered. Now, the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge has left residents feeling cut off on the north side of the harbor, wondering what the future may hold for their home.

Mr. Morton was hired by Bethlehem Steel on June 25, 1970. At its height, the mill on Sparrows Point employed 31,000 people. He was signing on to a legacy company in a town with a rich history. Construction on the mill began in 1887, built on a salt marsh. For over a century it powered the local community, building a company town modeled after the industrial towns of New England. Schools, stores, a hospital, even a police force – everything was operated by the mill. Mr. Morton planned to work there for only one summer. He stayed over 40 years.

With all eyes on the wreckage of Key Bridge, Sparrows Point has reentered the spotlight. Today the mill is gone, replaced by warehouses for Amazon, Under Armour, and McCormick & Co. As the economic powerhouses driving the region shifted, so did the community ethos. Still central to that is the legacy of Bethlehem Steel, at one point the largest steel mill in America, which helped build World War II ships and iconic landmarks like the Golden Gate Bridge.

The history of the community forged by Bethlehem Steel is more than one of camaraderie and grit. It’s also one of civil rights struggles and unionizing. And its evolution from a past built from steel to a more uncertain future – from an economy founded on building stuff to one powered by buying stuff – is one that will echo with hollow familiarity in former manufacturing centers all over the United States.

“Baltimore has a reputation as an industry town and as a manufacturing town. But fundamentally, we’re a port town, and that’s one thing that the bridge’s collapse has really driven home,” says Anita Kassof, executive director of the Baltimore Museum of Industry.

Sparrows Point “was an absolutely self-contained town, segregated by economics and race. But it was such that the families of the mill workers were right there. So it really was like a family, both metaphorically and in fact,” says Ms. Kassof.

The company town was demolished in the 1970s, and employees of Bethlehem Steel were left to relocate themselves. The land has long been redeveloped with small homes on winding streets in Edgemere, a neighborhood locals include in Sparrows Point. A wooded state park covers a stretch of coastline. The town is home to a dollar store, a senior center, and a handful of bars and restaurants. Across the creek is Turner Station. Bethlehem Steel’s Black employees lived in the neighborhood of small brick row houses during the decades when the work crews and neighborhoods were segregated, something Mr. Morton recalls.

“Everybody used to work at the mill”

Though the mill closed in 2012, many residents of Sparrows Point and Turner Station worked there or have family members who did. “Everybody used to work at the mill,” says Jim Rehak, a contractor from Sparrows Point.

Kimberly Schoeberlein and her husband live on a street in Edgemere named after her husband’s family. His grandfather was a heater at Bethlehem Steel.

The Key Bridge was another point of local pride. When it collapsed last week, it felt personal to many here – and its absence has isolated them. Mr. Rehak commutes across the harbor for a job in Annapolis. It now takes him nearly twice as long.

“We lost a major artery to get to the rest of the world,” says Ms. Schoeberlein. “It feels like we’re disconnected.”

A real estate agent in Sparrows Point, she has already spoken to people concerned about property values and some considering moving across the harbor.

The bonds have remained strong for Mr. Morton and other former Bethlehem Steel employees who still live in Sparrows Point and Turner Station. Mr. Morton, in particular, has never strayed far from the legacy of the mill. In the 1990s, he took a computer science college class. He learned coding and built a training module that the company paid to use for new workers – making him a union worker with an outside contract. Since the mill closed, Mr. Morton, who has a photographic memory and used to stay after work to sketch machines, built a complete virtual reality model of the mill, down to the nuts and bolts.

He and others also remember the less idyllic parts of the past – the racism and segregation.

“I wasn’t the typical ’60s and ’70s Black employee,” says Mr. Morton. “I would never have been able to handle the discrimination that those guys had to take.”

Mr. Morton’s own relationship with his fellow steelworkers was often mentor-mentee. “Some of those guys took me under their wing and became like fathers to me.”

“I think we’re going to lose our little town”

Bill Barry, a retired labor studies professor and local historian, has interviewed more than 100 former steelworkers. They were divided evenly on whether they would want their children to work there. “Your grandfather worked there; your father worked there; you could work there,” he says.

That sense of pride mixed with resentment for some when the company declared bankruptcy and finally closed.

“They all went to the same schools; they went to the same churches. It was a traditional American industrial community,” says Mr. Barry. “Everybody knew everybody around, and I don’t think that’s true anymore. Communities have fractured.”

To some, like Mr. Morton, the departure of the mill has contributed to a loss of local identity. Darlene Lumpkin, who grew up in Sparrows Point, sees a similar pattern. She loves the area, calling it her “Mayberry,” but traffic and redevelopment feel like they’re taking over. “I think we’re going to lose our little town,” she says.

Baltimore is the westmost port on the East Coast, says Ms. Kassof. The companies now operating out of Sparrows Point – which also include FedEx and Harley Davidson – require a different type of labor and produce a different product, she notes. But they chose the location for many of the same reasons as Bethlehem Steel: the deepwater port and easy access to roads and railroads headed to the Midwest.

In all, more than 12,000 people work at the warehouses and other businesses that occupy the old mill site.

The flavor of Sparrows Point, no longer loyal to a single employer, is changing. “The steel industry was incredibly skilled,” says Mr. Barry. “People were proud of it. I’m not sure that the work that’s there now has that kind of skill.”

The Schoeberleins used to be able to see the bridge from their bedroom window. Today, the empty sky is a constant reminder that, at least for now, they’re isolated. The collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge has turned their focus even more to their immediate community. Ms. Schoeberlein sits on a local business owners board, where members are trying to anticipate needs that Sparrows Point might fill or ways the community could adapt to a possible influx of workers here to rebuild the bridge.

For Mr. Morton, it was his fellow steelworkers who first made him feel like this was his home. “The guys that trained me – I call them my blast furnace fathers,” he says.

They were bonded by a shared sense of danger, thrill, and pride. “We workers had that feeling of a kind of invincibility – that we were the big boys on the block and no one could topple us,” he says. “I remember older workers telling me, ‘Maryland can’t survive without Bethlehem Steel.’”